Skip to product information

1

/

of

1

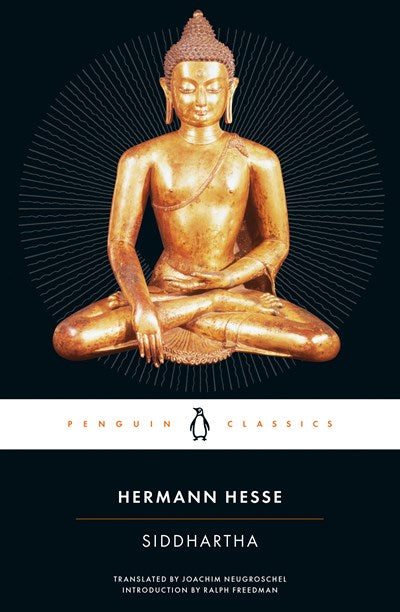

Siddhartha: An Indian Tale Spiral-Bound | January 1, 1999

Hermann Hesse, Joachim Neugroschel (Translated by), Ralph Freedman (Introduction by)

★★★★☆+ from 50,001 + ratings

$17.68

-

Free Shipping

Siddhartha: An Indian Tale

1

/

of

1

A bold translation of Nobel Prize-winner Herman Hesse's most inspirational and beloved work, which was nominated as one of America’s best-loved novels by PBS’s The Great American Read

A Penguin Classic

Hesse's famous and influential novel, Siddartha, is perhaps the most important and compelling moral allegory our troubled century has produced. Integrating Eastern and Western spiritual traditions with psychoanalysis and philosophy, this strangely simple tale, written with a deep and moving empathy for humanity, has touched the lives of millions since its original publication in 1922. Set in India, Siddhartha is the story of a young Brahmin's search for ultimate reality after meeting with the Buddha. His quest takes him from a life of decadence to asceticism, through the illusory joys of sensual love with a beautiful courtesan, and of wealth and fame, to the painful struggles with his son and the ultimate wisdom of renunciation. This new translation by award-winning translator Joachim Neugroschel includes an introduction by Hesse biographer Ralph Freedman.

For more than seventy years, Penguin has been the leading publisher of classic literature in the English-speaking world. With more than 1,700 titles, Penguin Classics represents a global bookshelf of the best works throughout history and across genres and disciplines. Readers trust the series to provide authoritative texts enhanced by introductions and notes by distinguished scholars and contemporary authors, as well as up-to-date translations by award-winning translators.

A Penguin Classic

Hesse's famous and influential novel, Siddartha, is perhaps the most important and compelling moral allegory our troubled century has produced. Integrating Eastern and Western spiritual traditions with psychoanalysis and philosophy, this strangely simple tale, written with a deep and moving empathy for humanity, has touched the lives of millions since its original publication in 1922. Set in India, Siddhartha is the story of a young Brahmin's search for ultimate reality after meeting with the Buddha. His quest takes him from a life of decadence to asceticism, through the illusory joys of sensual love with a beautiful courtesan, and of wealth and fame, to the painful struggles with his son and the ultimate wisdom of renunciation. This new translation by award-winning translator Joachim Neugroschel includes an introduction by Hesse biographer Ralph Freedman.

For more than seventy years, Penguin has been the leading publisher of classic literature in the English-speaking world. With more than 1,700 titles, Penguin Classics represents a global bookshelf of the best works throughout history and across genres and disciplines. Readers trust the series to provide authoritative texts enhanced by introductions and notes by distinguished scholars and contemporary authors, as well as up-to-date translations by award-winning translators.

Publisher: Penguin Random House

Original Binding: Trade Paperback

Pages: 176 pages

ISBN-10: 0141181230

Item Weight: 0.3 lbs

Dimensions: 5.0 x 0.5 x 7.7 inches

Customer Reviews: 4 out of 5 stars 50,001 + ratings

By the Winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature

In the 1960s, especially in the United States, the novels of Hermann Hesse were widely embraced by young readers who found in his protagonists a reflection of their own search for meaning in a troubled world. Hesse’s rich allusions to world mythologies, especially those of Asia, and his persistent theme of the individual striving for integrity in opposition to received opinions and mass culture appealed to a generation in upheaval and in search of renewed values.

Born in southern Germany in 1877, Hesse came from a family of missionaries, scholars, and writers with strong ties to India. This early exposure to the philosophies and religions of Asia—filtered and interpreted by thinkers thoroughly steeped in the intellectual traditions and currents of modern Europe—provided Hesse with some of the most pervasive elements in his short stories and novels, especially Siddhartha (1922) and Journey to the East (1932).

Hesse concentrated on writing poetry as a young man, but his first successful book was a novel, Peter Camenzind (1904). The income it brought permitted him to settle with his wife in rural Switzerland and write full-time. By the start of World War I in 1914, Hesse had produced several more novels and had begun to write the considerable number of book reviews and articles that made him a strong influence on the literary culture of his time.

During the war, Hesse was actively involved in relief efforts. Depression, criticism for his pacifist views, and a series of personal crises—combined with what he referred to as the “war psychosis” of his times—led Hesse to undergo psychoanalysis with J. B. Lang, a student of Carl Jung. Out of these years came Demian (1919), a novel whose main character is torn between the orderliness of bourgeois existence and the turbulent and enticing world of sensual experience. This dichotomy is prominent in Hesse’s subsequent novels, including Siddhartha (1922), Steppenwolf (1927), and Narcissus and Goldmund (1930). Hesse worked on his magnum opus, The Glass Bead Game (1943), for twelve years. This novel was specifically cited when he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1946. Hesse died at his home in Switzerland in 1962.

Calling his life a series of “crises and new beginnings,” Hesse clearly saw his writing as a direct reflection of his personal development and his protagonists as representing stages in his own evolution. In the 1950s, Hesse described the dominant theme of his work: “From Camenzind to Steppenwolf and Josef Knecht [protagonist of The Glass Bead Game], they can all be interpreted as a defense (sometimes also as an SOS) of the personality, of the individual self.”

Joachim Neugroschel (translator) has won three PEN translation awards and the French-American translation prize. He has also translated Thomas Mann's Death in Venice and Sacher-Masoch's Venus in Furs, both for Penguin Classics. He lives in Brooklyn, New York.

Ralph Freedman (introducer), Professor Emeritus of Comparative Literature at Princeton University, is acclaimed for his biographies Hermann Hesse: Pilgrim of Crisis, and Life of a Poet: Rainer Maria Rilke.

Born in southern Germany in 1877, Hesse came from a family of missionaries, scholars, and writers with strong ties to India. This early exposure to the philosophies and religions of Asia—filtered and interpreted by thinkers thoroughly steeped in the intellectual traditions and currents of modern Europe—provided Hesse with some of the most pervasive elements in his short stories and novels, especially Siddhartha (1922) and Journey to the East (1932).

Hesse concentrated on writing poetry as a young man, but his first successful book was a novel, Peter Camenzind (1904). The income it brought permitted him to settle with his wife in rural Switzerland and write full-time. By the start of World War I in 1914, Hesse had produced several more novels and had begun to write the considerable number of book reviews and articles that made him a strong influence on the literary culture of his time.

During the war, Hesse was actively involved in relief efforts. Depression, criticism for his pacifist views, and a series of personal crises—combined with what he referred to as the “war psychosis” of his times—led Hesse to undergo psychoanalysis with J. B. Lang, a student of Carl Jung. Out of these years came Demian (1919), a novel whose main character is torn between the orderliness of bourgeois existence and the turbulent and enticing world of sensual experience. This dichotomy is prominent in Hesse’s subsequent novels, including Siddhartha (1922), Steppenwolf (1927), and Narcissus and Goldmund (1930). Hesse worked on his magnum opus, The Glass Bead Game (1943), for twelve years. This novel was specifically cited when he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1946. Hesse died at his home in Switzerland in 1962.

Calling his life a series of “crises and new beginnings,” Hesse clearly saw his writing as a direct reflection of his personal development and his protagonists as representing stages in his own evolution. In the 1950s, Hesse described the dominant theme of his work: “From Camenzind to Steppenwolf and Josef Knecht [protagonist of The Glass Bead Game], they can all be interpreted as a defense (sometimes also as an SOS) of the personality, of the individual self.”

Joachim Neugroschel (translator) has won three PEN translation awards and the French-American translation prize. He has also translated Thomas Mann's Death in Venice and Sacher-Masoch's Venus in Furs, both for Penguin Classics. He lives in Brooklyn, New York.

Ralph Freedman (introducer), Professor Emeritus of Comparative Literature at Princeton University, is acclaimed for his biographies Hermann Hesse: Pilgrim of Crisis, and Life of a Poet: Rainer Maria Rilke.